Haiti Sinking Deeper Into Catastrophe: Who Will Save it?

ST. JOHN’S, Antigua – Haiti has never been far from widescale human suffering, grave political instability, and grim economic underdevelopment. But its circumstances today are worse than they have been before.

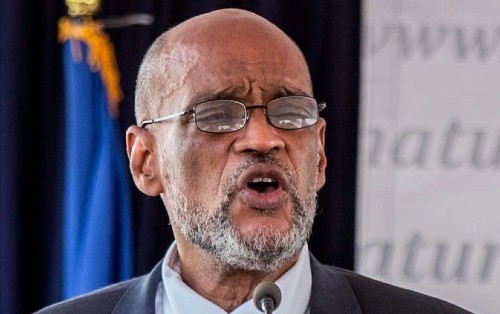

Haiti Prime Minister Ariel HenryThe country has become a battleground for rival criminal gangs whose weapons are superior to those of the police, both in quantity and firepower. These gangs have established fiefdoms in which they rule supreme, terrorizing communities, kidnapping people, demanding huge ransoms, committing vile murders and even burning their victims alive or dead. Even more disturbing, some gangs appear to have established links with politicians.

Haiti Prime Minister Ariel HenryThe country has become a battleground for rival criminal gangs whose weapons are superior to those of the police, both in quantity and firepower. These gangs have established fiefdoms in which they rule supreme, terrorizing communities, kidnapping people, demanding huge ransoms, committing vile murders and even burning their victims alive or dead. Even more disturbing, some gangs appear to have established links with politicians.

Beyond the loss of control of law and order, the country is being governed, in name, by unelected officials with no independent judiciary or a functioning national assembly. An accord among civil society groups and political players, fashioned in September 2021, has collapsed. This makes fulfillment of the desire for a Haitian-led solution to the country’s problems most unlikely, and not credible.

What makes this situation worse is that Haiti has no strong institutions to support governance and to address the deep-seated problems of the country.

Some nations – among them countries whose governments have contributed to the underdevelopment and weakness of Haiti – now conveniently hide behind the Haitian call for a “Haitian-led” solution, to do little or nothing. The United Nations (UN) withdrew its Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) in October 2017, after 13 years.

Despite the dire situation which now exists, the UN Security Council opted to extend the mandate of its Integrated Office in Haiti (BINUH) until July 15, 2023, but not to expand it to tackle the spiral of violence, lawlessness, and terror of armed gangs.

Against this background, Luis Almagro, the Secretary-General of the Organization of American States (OAS), issued a rousing public indictment of the “international community” and the self-interested political elite in Haiti. Almagro minced no words when he declared: “The institutional crisis that Haiti is experiencing right now is a direct result of the actions taken by the country’s endogenous forces and by the international community”. He stated, unequivocally, that “the last 20 years of the international community’s presence in Haiti has amounted to one of the worst and clearest failures implemented and executed within the framework of international cooperation”. To be clear, “the international community” in Haiti amounted to a core group compromising the European Union, the UN, the OAS, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, and Spain.

I publicly agreed with his assessment. It was the most honest and compelling statement by a high official of any regional or international institution ever issued, concerning Haiti. In agreeing with his statement, I interpreted his definition of the “international community” as including every country, every international financial and development institution, the United Nations and its organs, and the OAS itself. But I also recognized then, what I later said in the Permanent Council of the OAS on August 17, when the Foreign Minister of Haiti Jean Victor Généus, clearly prompted by Almagro’s statement, asked for a meeting.

What I said, in brief, was that “many countries in the international community are perfectly innocent of what happens in Haiti or has happened there. There are others – both countries and institutions – that have damaged Haiti irreparably over many years. Now, it is up to those countries to do something to correct the situation. Financial support is the obligation of those members of the international community with the resources to do so. And many of them, incidentally, bear responsibility for the situation in Haiti today”.

Almagro is clearly right in saying, “…resources have to be provided to Haiti through an institutionalized process by the international community, with a strong monitoring component and capacity to combat corruption and prevent the resources from being diverted and misused”.

As I observed at the OAS meeting, Haiti cannot expect an international response to its needs without some assurance that, within the country, there will be a collective, solidified position, both in terms of the requests they make, the cooperation they will give, and the openness with which they will deal with the international community.

For his part, Foreign Minister Généus said that the Government has tried to promote dialogue, suggesting that its efforts have not been successful, but that “the Prime Minister will continue tirelessly in this quest for dialogue and consensus”.

Of course, such a dialogue will not happen, nor will any agreement be sustained, unless there is good offices mediation to facilitate it and oversee the implementation of its agreements. Mediation cannot happen without an invitation from the Ariel Henry provisional government and the agreement of the other Haitian groups.

Neighboring countries are already struggling with the failure of the Haitian State. The Bahamas, with a population of 400,000, has an estimated 150,000 Haitian refugees in its territory. This year alone, the Bahamas Government has spent millions of dollars repatriating Haitian refugees. In the words of the Ambassador of the Dominican Republic to the OAS, Josue Fiallo, the situation in Haiti “constitutes an unusual and extraordinary threat to my country’s national security, foreign policy and economy”. Additionally, the US has deported or expelled thousands of Haitians fleeing from their desperate conditions.

In his statement of August 8, Almagro identified what amounts to a program of action to try to save Haiti. It includes: bringing violence under control and disarming the gangs; providing technical and financial resources to address the current security situation; creating a central mechanism to deploy assistance without overlapping and wasteful efforts; a strong monitoring component to combat corruption; drafting a new Constitution that fixes deficiencies in the existing constitution, including by establishing an autonomous Central Bank, an independent justice system, a functioning and effective education system; and investment to create employment and alleviate poverty.

Few would disagree with this agenda. The questions it raises are: who would provide the financing and which agency would be trusted to implement it?

These are questions, which must be addressed before Haiti sinks even deeper into an even bigger catastrophic humanitarian crisis than it has suffered so far. Haiti must become a priority on the agenda of all international and regional bodies – now.

*Sir Ronald Sanders is Antigua and Barbuda’s Ambassador to the United States of America and the Organization of American States. He is also a Senior Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, and Massey College in the University of Toronto