Silent Power: How Antiguan Farmers Are Rewiring Energy, Water and Survival

ST. JOHN’S, Antigua – At the entrance to Neil Gomes’s farm in McKinnon’s, water is moving.

Antigua and Barbuda Meteorological Services.Rows of young cucumber plants are being irrigated by drip lines, moisture spreading evenly across the thirsty soil. Leaves glisten. Hoses pulse lightly. But the familiar racket that usually accompanies this scene on Caribbean farms is missing. No diesel engine rattles. No sharp mechanical clatter cuts through the morning air.

Antigua and Barbuda Meteorological Services.Rows of young cucumber plants are being irrigated by drip lines, moisture spreading evenly across the thirsty soil. Leaves glisten. Hoses pulse lightly. But the familiar racket that usually accompanies this scene on Caribbean farms is missing. No diesel engine rattles. No sharp mechanical clatter cuts through the morning air.

Instead, there is only a low, almost imperceptible hum — so soft that the sound of birds and insects waking up around the fields quickly overtakes it.

A pump, unobtrusive and sitting near the entrance, draws power directly from the sun. It works quietly, steadily, without fuel deliveries, without exhaust, without the constant maintenance that farmers like Gomes once accepted as unavoidable.

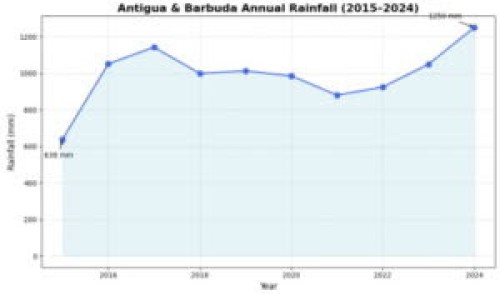

The country’s shift away from fossil fuels is often discussed in megawatts, timelines, and national targets. But on a small, water-scarce island with no rivers, no freshwater lakes, and rainfall that is increasingly unreliable, the transition is not abstract. It is immediate and physical. It determines whether crops survive a dry season, whether a farmer plants confidently or cautiously, and whether agriculture expands or contracts.

For farmers like Gomes, the energy transition is about control in a region that accounts for seven of the world’s 36 most water-stressed countries. In Antigua and Barbuda, each person has access to approximately 566 cubic metres of renewable water (rainfall, etc.) resources per year, just half of what international experts consider the minimum needed to avoid water stress. Farmer Neil Gomes opening the pipe to his 5000-gallon water bladder, at his McKinnons Farm in Antigua. (CMC/ Roseann Pile Photo)

Farmer Neil Gomes opening the pipe to his 5000-gallon water bladder, at his McKinnons Farm in Antigua. (CMC/ Roseann Pile Photo)

That works out to roughly 150,000 one-gallon bottles of water—everything a person would have to rely on for drinking, cooking, washing, farming, and sanitation for an entire year.

Culturally, crops in Antigua and Barbuda are predominantly rain-fed. So, the startling figure above leaves the agricultural sector highly vulnerable to variable and unpredictable rainfall.

Gomes bends over a bed of cucumbers, inspecting leaves, measuring growth with the practiced eye of someone who has done this work for over three decades. On his 12-acre farm in northwestern Antigua, he has coaxed cantaloupes, tomatoes, cabbage, peppers, squash, and other vegetables from soil that cracks under prolonged sun.

Gomes bends over a bed of cucumbers, inspecting leaves, measuring growth with the practiced eye of someone who has done this work for over three decades. On his 12-acre farm in northwestern Antigua, he has coaxed cantaloupes, tomatoes, cabbage, peppers, squash, and other vegetables from soil that cracks under prolonged sun.

Fitzmorgan Greenaway stands on top of the biogas dome, looking at the nutrient‑rich liquid fertilizer that flows out as effluent. (CMC / Roseann Pile Photo)The Quiet Revolution: Solar Irrigation and the New Economics of Farming

Fitzmorgan Greenaway stands on top of the biogas dome, looking at the nutrient‑rich liquid fertilizer that flows out as effluent. (CMC / Roseann Pile Photo)The Quiet Revolution: Solar Irrigation and the New Economics of Farming

“I’ve been doing this 30-plus years,” he says quietly. “And what I soon learned was this: if you don’t have water, you don’t have farming. You simply don’t.”

Armed with this truth, Gomes built three ponds on his land over the years, trying to capture and store rainfall. But evaporation during the dry season often outpaced replenishment. The hotter the season, the faster the water disappeared.

Buying water from the national utility, APUA, was expensive.

“In the dry season,” he says, “I’d have to scale down production. You couldn’t afford not to.”

That calculation, planting according to uncertainty rather than need, shaped agriculture across the island. Farmers reduced risk by reducing output. Food production continued, but growth stalled, and shortages became the norm during the dry season.

This was not a failure of effort. It was a structural constraint.

What began to change that equation was not a single innovation, but a framework that treated water, energy, and food as inseparable.

In 2021, Antigua and Barbuda joined Barbados, Jamaica, and St. Kitts and Nevis under the Mexico–CARICOM–FAO Resilient Caribbean Initiative, built around the Water–Energy–Food Nexus. The idea was straightforward but transformative: farmers could not solve water problems without addressing energy, and food security could not improve without stabilising both. Brent Simon (Photo)

Brent Simon (Photo)

Gomes, known for his reputation as a dedicated and experienced producer, was among 12 farmers selected in Antigua and Barbuda for support. Twenty-six others received training on solar-powered drip irrigation. What arrived at his farm did not look revolutionary: a 5,000-gallon water bladder, a solar-powered pump, and solar panels.

But functionally, it changed everything. Irrigation became consistent, predictable, and scalable.

“I don’t have to hope for rain anymore,” Gomes says. “I manage water now.”

The shift away from diesel was immediate. Fuel costs dropped. Maintenance demands declined. The noise and vibration that once accompanied irrigation disappeared. Farming became quieter — literally and figuratively.

“If you’d asked me before, would I choose solar? — I’d have said no. I would have thought it too costly,” he admits. “But having it? It changed how I farm.

The veteran tracked the results carefully. In the first months, yields increased by about six percent — simply from reliable irrigation. Over time, as the system became integrated into full planting cycles, yields climbed nearly 50 percent above pre-solar levels.

That jump transformed the farm’s economics. Conservative estimates put fuel savings between $700 and $1,000 annually. More importantly, planting decisions were no longer dictated by fear of water shortages.

There were environmental benefits, too. Diesel pumps became backups rather than defaults. Emissions dropped. So did noise.

“That feeling,” he says, “of knowing you’re not heavily participating in harming the environment… that stays with you.” He pauses, looking out over the rows. “We leave something for the young ones.”

Gomes didn’t just adopt the technology — he became an evangelist for it. Other farmers come to his farm to see the solar pump in action. He speaks openly about costs, benefits, and limitations. For him, farmers adopting climate-smart practices isn’t just good business — it’s a legacy.

Schoolchildren also visit and learn about how agriculture and technology intersect. He teaches them that farming isn’t backbreaking work alone; it’s innovation, resilience, and adaptation.

Two years ago, he took his experience to the Caribbean Week of Agriculture, explaining the water-energy nexus not in theory, but in practice.

Exposure, he believes, is what makes transition possible.

“If I didn’t see it working,” he says, “I might never have changed.”

Energy from Waste: A Farm Where Power Is Grown, Not Bought

That same principle applies further south, inland, at Table Hill Gordon in St. Paul, where another form of energy transition has been quietly operating for years.

When arriving at FARAGA Farms, there is no imposing structure announcing innovation. No industrial installation. No visual statement of modernity. The land unfolds gradually: fruit trees, drainage channels, crop plots arranged with deliberation.

For over forty years, this has been Fitzmorgan Greenaway’s terrain.

The name FARAGA is not branding. It is family history — the first letters of each family member’s name, bound by the “G” of Greenaway. The farm covers seven acres at Table Hill Gordon, with a total of 17 acres cultivated across Antigua. Tomatoes are a specialty. Sweet potatoes, cassava, cucumbers, and other staples fill out production.

“We try not to do too much of everything,” he says. “We do a few crops, and we try to do them well.”

Greenaway has always prioritised infrastructure that supports longevity: roads, drainage, and water control. He carefully manages a nearby natural water source, expanding or deepening ponds as conditions require.

“At FARAGA,” he says, “water is about movement — holding it when you need it, releasing it when you don’t.”

That logic extends to energy.

Greenaway also raises livestock — pigs, cattle, and sheep — scaling numbers to demand rather than optimism. He gave up goats after repeated theft, stressing that efficiency governs every decision.

It was the pigs that drew attention from a Chinese technical delegation working with Antigua and Barbuda’s Ministry of Agriculture about a decade ago. They were looking to pilot biogas systems to convert agricultural waste into usable energy.

“They saw the pigs,” Greenaway recalls.

What followed was a collaboration among Chinese technicians, Ministry officials, and local farmers to build a biogas digester on the farm. FARAGA became a demonstration site for weeks.

The finished system was modest, and that makes it significant.

The cylindrical digester sits quietly among trees and fields, six feet across and deep, capped with a dome that collects methane-rich biogas produced as microorganisms break down organic waste in the absence of oxygen. Water levels rise and fall naturally as gas pressure builds and releases. The underground chamber digests waste fed in through an inlet and pushes nutrient-rich effluent out through an outlet, providing both fuel and fertilizer in a simple, self-contained system.

Gas produced powers a stove. Food is boiled. Lights illuminate pigpens at night.

Energy that once had to be purchased is now generated on site.

“It worked out very nice for us,” Greenaway says simply.

The system remains operational years later. It is not something he would have installed independently.

“No,” he says. “Not free-handedly.”

What made it viable was guidance, demonstration, and understanding, he explained — the same factors that enabled Neil’s adoption of solar irrigation.

Both men agree that transition occurs when people see systems rather than just hear descriptions.

At FARAGA Farms, sustainability predates the language used to describe it. Simplicity is not aesthetic; it is practical. Every square foot matters. Infrastructure must coexist with crops, water channels, and movement patterns.

This restraint mirrors the broader direction of Antigua and Barbuda’s agricultural transition: targeted, site-specific solutions rather than sweeping overhauls.

From Pilot Projects to Policy: Rewiring the National Food System

National initiatives are beginning to reflect that thinking.

In September 2025, Antigua launched a solar-powered desalination pilot in Jennings, Blubber Valley, using Nanophotonics Enhanced Direct Solar Membrane Distillation technology developed with the University of Texas at El Paso. The system converts brackish groundwater into irrigation water using sunlight, producing up to two cubic meters per day, with additional concentrate suitable for hardier crops.

For a country where freshwater scarcity is structural, not seasonal, the implications are significant.

“This project gives farmers access to water when they otherwise would have none,” said Brent George, Projects Coordinator at the Ministry of Agriculture, at the launch.

FAO National Project Coordinator Luke Nedd described it as resilience-building, enabling farmers to continue producing even during drought.

Together, solar pumps, biogas systems, and desalination pilots form a coherent pattern. They show how Antigua and Barbuda is reducing its reliance on fossil fuels not through spectacle, but through systems that operate within local constraints.

Back at McKinnon’s, the solar pump continues its near-silent work.

“At first,” Neil says, “you don’t notice the difference. And then you realise everything has changed.”

At Table Hill Gordon, Greenaway continues managing water, waste, and energy with the steadiness of long experience.

“There’s a lot happening in the world,” he says. “And we have to provide food for ourselves.”

Between these two farms lies one aspect of the story of Antigua and Barbuda’s energy transition — not loud, not grand, but deliberate.